October 17th 2022

South Korea

Traveler: Nayun Hong

Destination: South Korea

Following graduation from the University of Notre Dame, Nayun returned to her birthplace of South Korea to spend time with her grandparents in their hometown. For six weeks, she explored the architecture, urban fabric, and natural landscapes of many cities and time periods, ranging from 14th century pavilions in coastal cities to 20th century post-war neighborhoods on the foothills of mountains.

A trip that was delayed two years due to the pandemic, I finally had a chance to return to South Korea this summer. My grandparents recently moved back to their hometown of Jecheon, a city in central South Korea two hours away from the capital city of Seoul (or one hour high-speed train ride). Jecheon is most famous for its natural attractions, one of them being the Uirimji reservoir created during the Three Kingdoms period (57 BC to 668 AD).

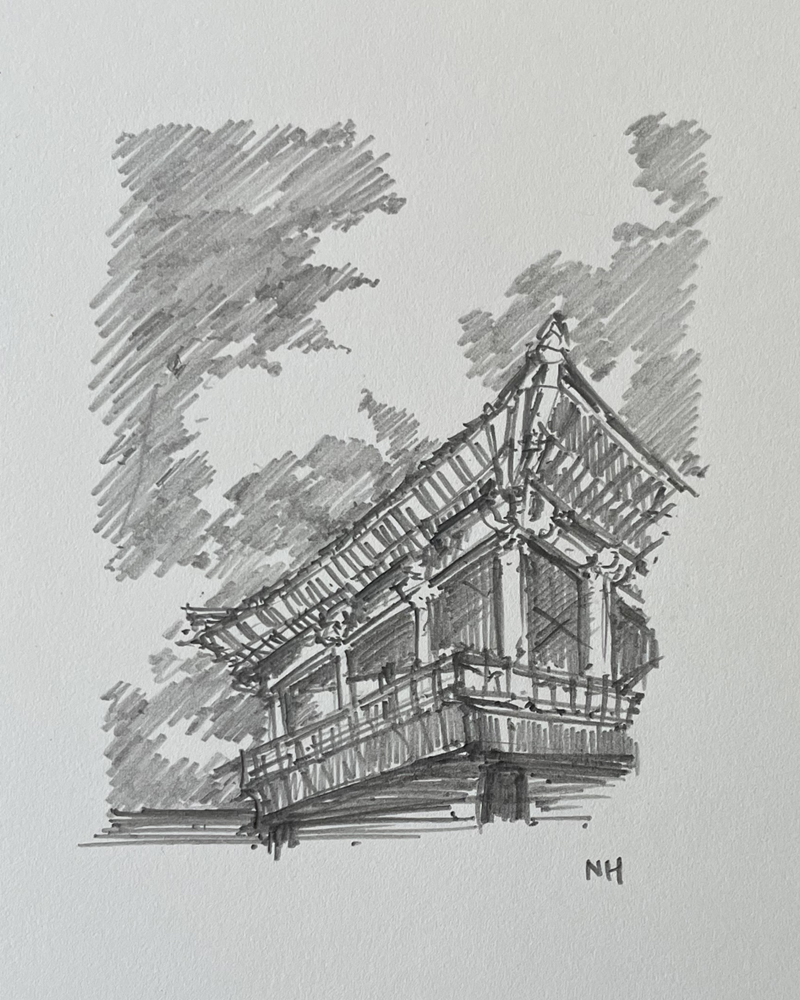

The reservoir is home to other natural and architectural features, such as a 30-meter (100 ft) tall waterfall, ancient pine and willow trees, and pavilion structures showcasing traditional timber joinery and painted floral motifs. We visited the Uirimji and a smaller neighboring reservoir, Biryongdam, a couple of times during my stay and enjoyed morning and evening walks along the waters.

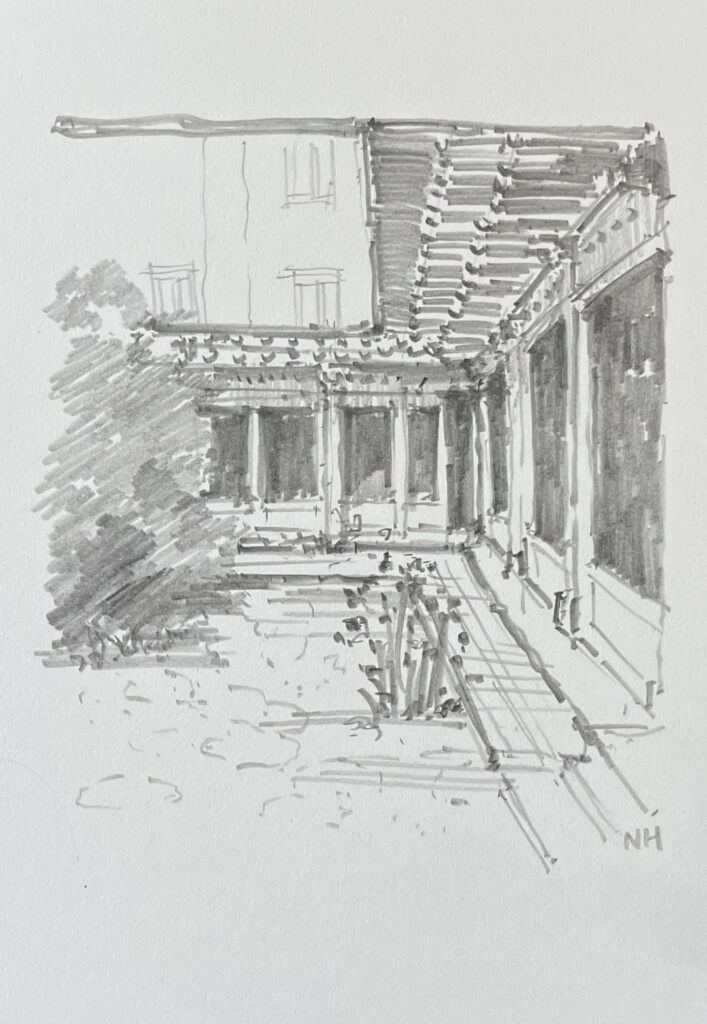

The Cheongpung Cultural Heritage Complex is another famous site in Jecheon. The buildings in the complex were originally located in the lower valley of its current location, which was flooded in 1985 for the creation of the Chungju Dam and lake. To preserve the architectural and cultural history of this village, buildings and artifacts were relocated to the upper valley and arranged as an outdoor museum. Although not the original location, the buildings felt right at home and in tune with their landscape, especially the pavilions. They were perched atop mountain peaks to provide scenic lookout points or tucked away between groves of trees as secluded shelters for rest and contemplation, as these traditional pavilions originally served as study spots for Confucian scholars.

This visit was a great opportunity for me to see and experience firsthand the vernacular language of traditional Korean houses, or hanoks, which I researched heavily as part of my undergraduate thesis project.

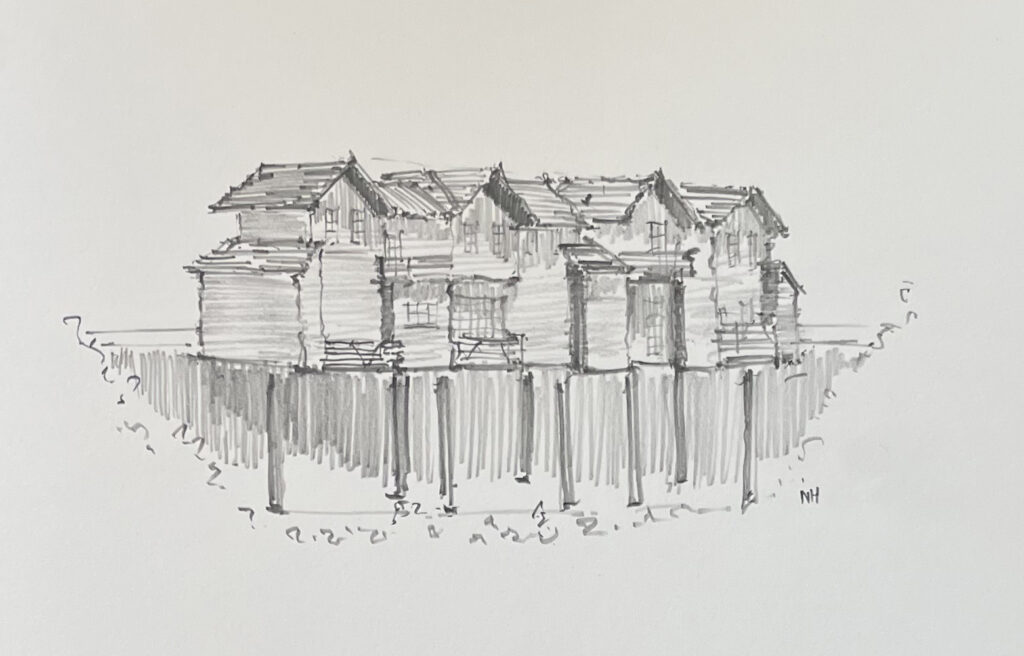

Thanks to Jecheon’s proximity to Seoul, I visited the capital city twice during my stay. My first destination was the Ihwa Mural Village, one of some remaining hilltop daldongnaes in South Korea. The name literally translates to ‘moon village’, originating from its elevated location and closer reach and view of the moon. Daldongnaes developed after the Korean War as refugees resettled on the mountain slopes which, according to traditional Korean planning principles, were not ideal settlement locations.

As Seoul continued to modernize rapidly in the 1990s and early 2000s, the neighborhood was slated for demolition and redevelopment into apartment complexes (this continues to the fate for many older urban neighborhoods and rural landscapes today). In efforts to preserve this fabric of modern Korean history, the neighborhood underwent a public art-themed project to revitalize the area as a cultural attraction, successfully bringing in new business and tourists. The meandering streets hugged by cafes and museums, whilst catching glimpses of the Namsan tower in the distance, was definitely worth the hike up the neighborhood.

The Ikseon-dong Hanok Village was probably my favorite destination during my visit to Seoul. I didn’t think the streets could get any narrower than those of the Ihwa Mural Village, but traveling further back in time with Ikseon-dong proved otherwise. This neighborhood was developed in the 1920s during the Japanese occupation. It served two purposes: one, the building of traditional Korean homes was an act of resistance under the Japanese government and, two, the development of these densely packed neighborhoods helped to relieve the growing population pressures in Seoul at the time.

The renovation of many of these houses as commercial spaces was a reaction to a period during the 1980s and 1990s when these single-family courtyard homes were destroyed in favor of multi-family buildings. Similar to the Ihwa Mural Village, these hanok neighborhoods were rebranded as cultural attractions to preserve hanok architecture and the traditional urban village fabric. It was fascinating to see how the interiors were renovated to maintain key hanok characteristics, while accommodating uses not originally meant for this building typology.

Not an architectural sight, but quite the urban feat: the Cheonggyecheon restoration project revitalized the Cheonggye stream, which was covered by a highway overpass for nearly 40 years, as a 6.8-mile public space. The stream flows west to east through downtown Seoul and ultimately joins the city’s main Han river. It’s an extremely successful urban restoration project that connects many cultural and historic monuments, parks, and plazas along its route. I walked half the path and was pleasantly surprised to find people hanging out under the bridges to escape the heat and a decent amount of foot traffic even on a rainy day. As the backdrop of the Seoul skyline changed along the route, so did the landscape design supporting the stream. At some points, it took on a more natural form with tall, uncut grass acting as buffers between me and the trout (schools of them, swimming in extremely clear waters in the middle of the city!); other times, the built landscape architecture was more evident with concrete steps leading into the water and fountains on the west end. The variety of public spaces provided a space for everyone, for all uses and needs at all times of the day.

A bonus photo: I walked westward and missed the sights on the east end, but this image from the internet shows a reproduction of the settlements that used to be here before the highway was built. After the Korean War, those left without homes settled on the banks of this stream and created makeshift houses. Eventually the stream banks became overcrowded, accumulated with trash, and the stream waters extremely polluted, pushing the city rid of these ‘slums’ by covering the stream with a highway.

At the end of my stay, I convinced my grandparents to join me on a trip to Gangneung, a city on the east coast of the peninsula. I’m so glad they did, because my grandpa had so many places he wanted to show me that I wouldn’t have known to visit otherwise. On our last day in Gangneung, he took us to the Gyeongpodae Pavilion. It was originally built in 1326 and relocated to its current location in 1508, which overlooks Gyeongpo lake and the beach beyond. Pavilions are common in the Korean landscape as the connection between man and nature was greatly valued in traditional Korean architecture. This is derived from the principles of pungsu, a Korean variation of feng shui. Gyeongpodae Pavilion is definitely one of the grander pavilions I’ve seen because of its various stepped levels. It has a unique three-section layout with a raised central floor flanked by higher terrace levels. I could have spent the whole day lounging on the upper terrace as it was the perfect spot for enjoying the coastal breeze, but we left after a good 45-minutes to enjoy some trout sashimi in Pyeongchang, where the 2018 Winter Olympics took place.

Having an educational background that mostly focused on Western classicism and traditional architecture, I find myself comparing those lessons to what I’ve learned (and continue to learn) about non-Western architecture and planning principles. There is so much to be learned from the vernacular and building traditions of other cultures and, despite being on opposite sides of the world, so many fundamental overlaps in what constitutes a good building, city, and environment.

Follow along our morning sketch exercises on Instagram, which also features Nayun’s trip, here: https://www.instagram.com/historicalconcepts_sketches/