August 29th 2017

Monticello

This is the final entry in a series on Parisian architecture and urban design’s influence on Thomas Jefferson and how France affected the built environment in America.

Our observer, Jacques Levet, Jr., culminates this series of posts about the relationship between Thomas Jefferson’s admiration for 1780s French architecture and Parisian urban planning to the evolution of American architecture with a visit to Monticello. In a previous entry, we saw how Jefferson’s personal travels in France were to profoundly influence him, and thus inspire some of this country’s earliest governmental buildings. But perhaps the best example of how his discoveries in Paris informed Jefferson’s work is found in his personal home.

Jefferson’s French influence on America

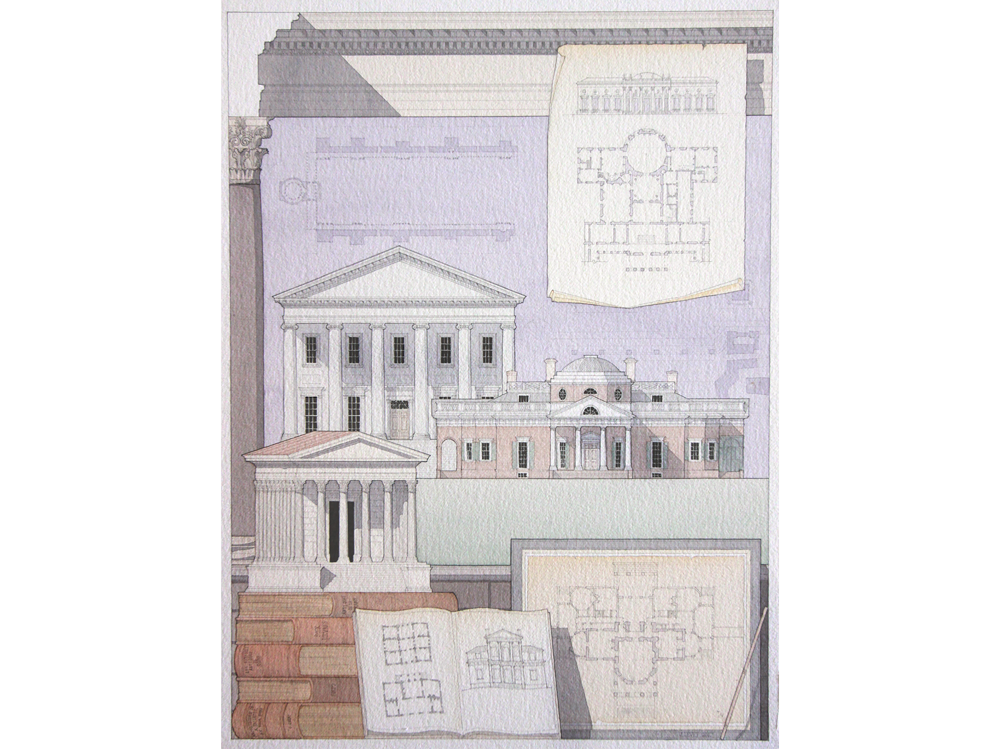

The watercolor above is an architectural rendering by Jacques, completed after his travels to Paris and Virginia, illustrating a selection of Thomas Jefferson’s designs and some of the French buildings that influenced his work.

Model of Monticello I

The design of Thomas Jefferson’s first Monticello, seen here in a model, was largely complete at the time of his departure for Europe and before his travels in France. By comparing his early design of the house to the Monticello we know today, you can see how Jefferson grew as an architect. (Click here, and follow the prompts for House, then Compare Monticello I and Monticello II for a Flash Animation of the two houses).

Monticello, view of east façade

While in Paris, Jefferson experienced numerous “modern” dwellings that utilized the classical language and the Parisian fascination with the neoclassical pavilion. Most of these homes, while multi-story, had what appeared to be a single-story façade. Upon his return from Paris in 1796, Thomas Jefferson tore off the upper level of his home and expanded its footprint, changing Monticello’s design to emulate the new homes of Paris.

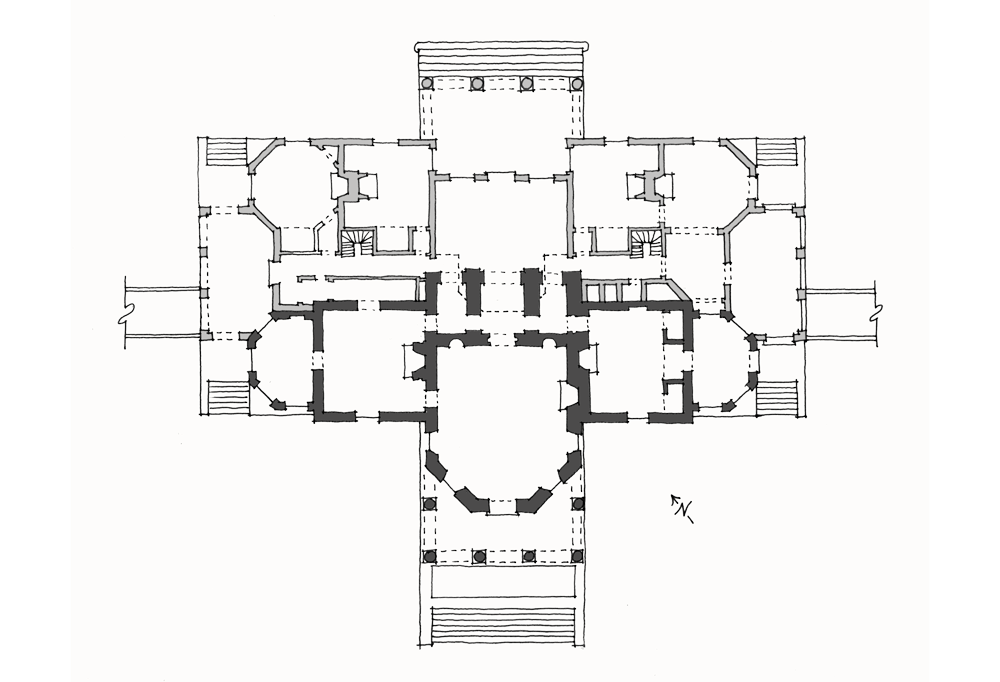

Plan diagram of Monticello

French planning allowed for the creation of grand public spaces separate from private rooms or utilitarian spaces. This was in marked contrast to most American homes of the time, including Thomas Jefferson’s first Monticello, where rooms were simple and not particularized for any specific function. The image above shows how Jefferson expanded his plan to allow for such spaces (the original footprint is indicated in dark gray).

Skylight detail from the interior (left) and view across the roof to the exterior of a skylight (right)

Not only did the innovation of Paris influence Monticello’s massing and plan, but also the addition of numerous details such as the skylights seen here, which were added to enable light to flood the interior spaces.

Peering into a family bedroom at Monticello

To achieve the appearance of a single-story on the façade, Jefferson tucked the family bedrooms in a mezzanine level around the larger, grander, public rooms of Monticello.

The Garden elevation of Monticello

Following a tradition which began with Louis le Vau’s Vaux-le-Vicomte, the Garden elevation of Monticello contains a projecting salon (known as the West Portico).

Panoramic view of Monticello

Like many of Jefferson’s works, Monticello seamlessly combines precedent from numerous sources; the projecting French salon is combined with the more English octagon and Roman details, while the French massing of the home is flanked with Palladian dependency wings (note the contrast to the mounds seen in the panoramic view of Poplar Forest in Post no. 6), just to name a few.

A last look at the south side of Monticello

The complexity in design at Monticello raised the standards for the ideal American residence. Although Thomas Jefferson never returned to Paris, he was successful in gathering together its lessons, and creating something of great personal meaning in his own home.

“All my wishes end, where I hope my days will end, at Monticello.” – Thomas Jefferson

| contributed by Jacques Levet |