August 18th 2017

Poplar Forest

This is the sixth in a seven-part series on Parisian architecture and urban design’s influence on Thomas Jefferson and how France affected the built environment in America.

In his second post from Virginia, our sightseer Jacques takes us to Poplar Forest. Towards the end of his public life, Thomas Jefferson sought respite from the bustle of Monticello and constructed a refuge about 90-miles southwest of his primary home. At Poplar Forest, Jefferson would once again meld examples he admired into the creation of something original and uniquely personal, and in this instance, he fully explored the octagonal shape. Unfortunately, although Jacques explored the inside of the house, he was not permitted to take photos within, so we will focus on the exterior.

The rear façade of Poplar Forest

Thomas Jefferson wrote that with the design of his personal retreat, he could create and follow “a fancy which I can indulge in my own case, although in a public work I feel bound to follow authority strictly.”

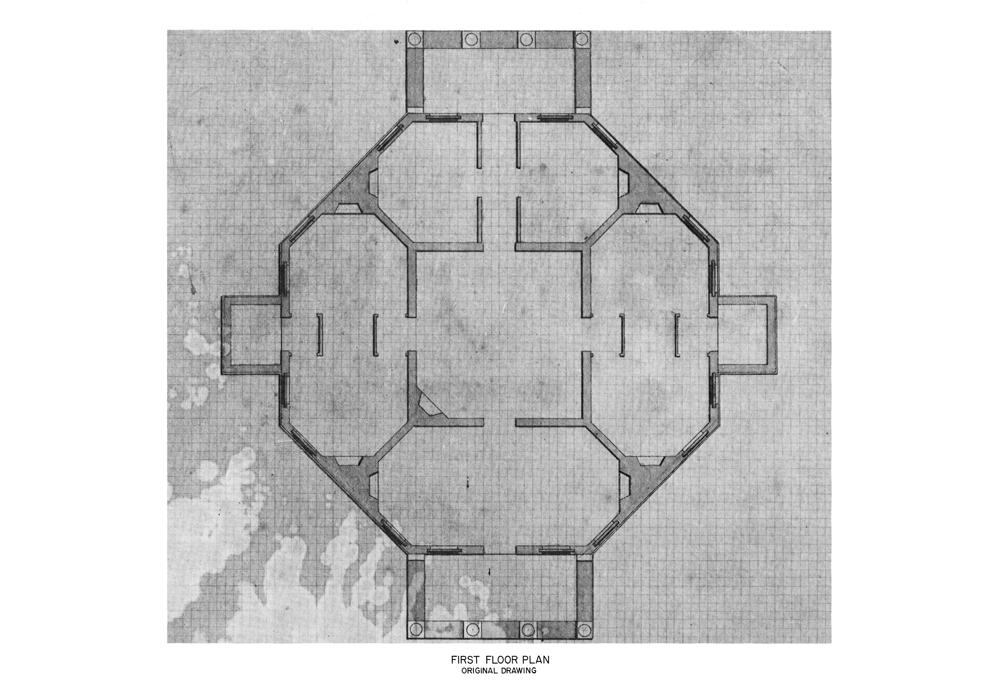

The Historic American Buildings Survey plan for the first floor of Poplar Forest

This structure, perhaps more than any other, best expresses Jefferson’s lifelong fascination with mathematics, the octagon, and other geometries he had observed in architecture from Palladian villas to French hotels. In this home, the central space is a perfect cube; extending 20’ in each direction, including towards the ceiling. Four elongated octagons surround the core, one on each side of the central room, which is lit by a skylight. Jacques notes that it is “pretty great to experience” although, the space does feel somewhat taller than a cube.

The front façade of Poplar Forest

Poplar Forest is like many of the French hotels Jefferson experienced while in Paris, particularly the Hôtel de Salm; it was designed to appear as a single-story home from the front, while it was in fact a two-story residence containing rooms of varying heights. An early American explorer, George Flower, remarked, “His house was built after the fashion of a French chateau. Octagon rooms, floors of polished oak, lofty ceilings, large mirrors, betokened his French taste, acquired by his long residence in France.”

A close-up view of the rear façade of Poplar Forest

The home also represents Thomas Jefferson’s ability to combine precedent from a variety of sources: Palladian concepts of massing and symmetry, British details in the plans and moldings, and many French elements such as skylights and alcove beds.

Panoramic view of Poplar Forest

As with Monticello, the most ornamental part of the grounds at Poplar Forest falls within a circular road surrounding the house. The octagonal structure is located at the center. Given the home’s modest size and budget, full Palladian service wings and massing like those seen at Monticello were neither appropriate nor functional here. Nonetheless, to emulate the effect he so admired, Jefferson utilized landscaping in place of architecture. A row of trees running east-west replaces the “wings.” These are connected to a mound constructed and planted on either side of the house, to bookend his composition, and in place of pavilions. This is a Jeffersonian interpretation of the Palladian integration of house and grounds.

The landscape at the front of Poplar Forest is known to have been “natural” in appearance, not unlike what was fashionable in English gardens of his time. But the gardens to the rear of Poplar Forest were far more geometric, like the house, featuring rows of trees and distinctly oval shrub beds. Perhaps this very different treatment was inspired by the contemporary landscapes Thomas Jefferson visited while Minister to France?

| contributed by Jacques Levet |