October 16th 2017

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston’s waterside views, breadth of history, unique urban character, and Southern charm draws in visitors from around the globe. Our traveler, Lora Shea, set off for Charleston, South Carolina one fine weekend with some friends. They wandered the streets of the historic district, ducking in and out of churches, commercial buildings, and residences along the way. In this blog post, Lora provides some history of the city and a glimpse at a few of the buildings which captured her imagination.

Standing on Broad Street looking down Church Street

Charleston has long been called ‘the Holy City’ due to its religious freedom and diversity, which began in the Colonial period. Throughout the city, church steeples provide way-finding vistas. Here, St. Phillip’s Episcopal Church is seen from Broad Street. St. Phillip’s was built in 1836 and designed by Joseph Hyde in the Wren-Gibbs tradition. The steeple was completed in 1850, designed by Edward Brickell White. The church represents the oldest religious congregation in South Carolina, established in 1681.

View of storefronts, nos 229-235 Meeting Street

Antebellum storefronts grace Charleston’s Meeting Street, around the corner from the famous Charleston City Market. The storefronts boast an array of eclectic details, often Italianate, such as cast-iron columns, modillions, and brackets with human mask motifs. In the 1970s and 1980s, efforts of the city to revitalize this area divided preservationists and citizens. A large hotel with restaurants was built across Meeting Street from the buildings shown, and preservationists considered the retention of the facades at 209-235 Meeting Street a major success.

In the garden of Two Meeting Street Inn

Two Meeting Street Inn sits on the corner of South Battery and Meeting Street, adjacent to The Battery, a seawall and promenade along the Charleston Harbor. The Queen Anne mansion was completed in 1892 for Waring Carrington, a Charleston jeweler, and his wife Martha Williams. The couple’s story of “love at first sight” has long inspired honeymooners who stay there.

The William Stone House on Rainbow Row, 83 East Bay Street

Rainbow Row, the longest cluster of Georgian row houses in the United States, was given its name in the 1930s and 1940s when the thirteen houses were restored and painted pastel colors, which help keep the houses cool. Originally the row houses had commercial uses on the ground floor with living quarters above; often with only exterior stairs in the rear yard to connect the first and second floor.

The William Stone House, shown in the foreground, was originally built around 1784 by a merchant who left Charleston for England during the Revolutionary War. The Neoclassical balcony was added in 1941 when owner Susan Pringle Frost (founder of the Preservation Society of Charleston) restored it as a dwelling. Image provided courtesy of Tyler Harbeson

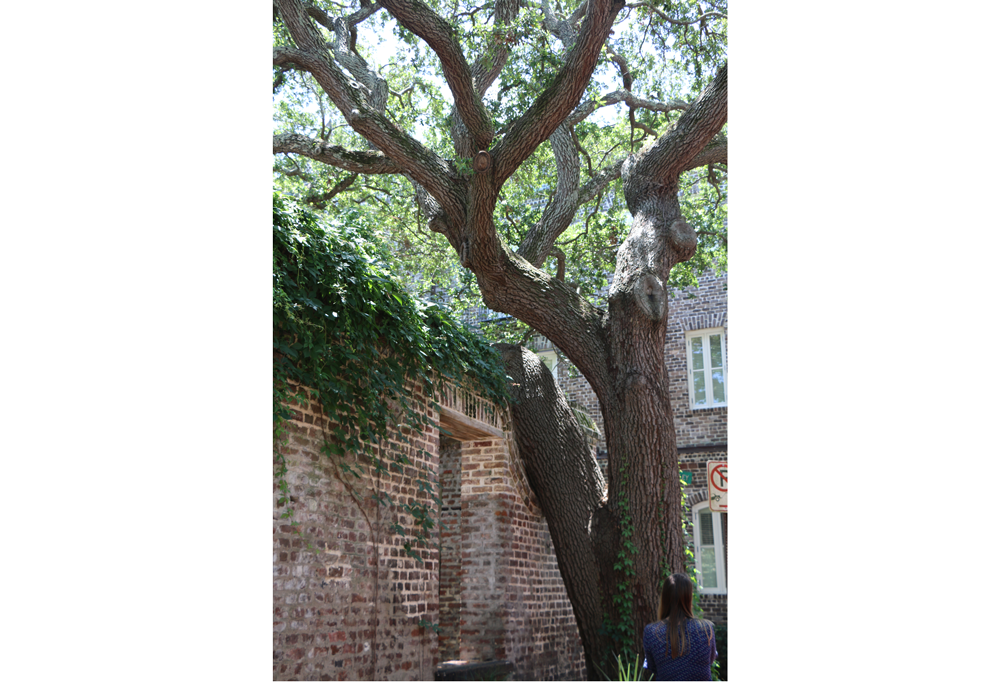

Elliott Street Oak Tree

The appeal of Charleston has as much to do with the gorgeous coastal landscape as it does the architecture. Here, on Elliot Street, the brick wall has been formed around a tree trunk, allowing them to live in harmony with each other. Image provided courtesy of Tyler Harbeson

Architectural Detail, YMCA Building / Women’s Exchange Building, 208 King Street

Richardsonian Romanesque ornamentation graces Charleston’s YMCA building, which was designed by S.W. Foulk and constructed in 1889 under contractor Henry Oliver. Foulk was a prominent designer of YMCAs in Victorian America. Here banded, rough-cut stone distinguishes store fronts on the ground floor, and pressed brick fills the second and third levels.

Architectural Detail, Two Meeting Street Inn

Whimsical Victorian details may be found throughout Charleston’s rich historical fabric. At Two Meeting Street Inn, an oriel window with fan-like ribbed support sits above porch columns. Image provided courtesy of Tyler Harbeson

Standing in the Double Parlor at the Aiken-Rhett House, 48 Elizabeth Street

Greek Revival moldings surround the mantle of this Double Parlor at the Aiken-Rhett House. The furniture is from Deming and Bulkley, a New York firm popular in Charleston at the time. The Aiken-Rhett House was built in 1820 and extensively renovated in 1833. From 1927 to 1972 the grand Federal-style home was owned and lived in by the Aikens, a wealthy antebellum family, until becoming a museum house in 1975. The home has been preserved as left by the last family member, with items from the family’s life and travels abroad decorating the rooms and wallpaper peeling in a state of dignified disrepair.

Stair at the Aiken-Rhett House, 48 Elizabeth Street

The Aiken-Rhett House has several staircases meant to give the family, guests, and service separate paths of circulation throughout the house.

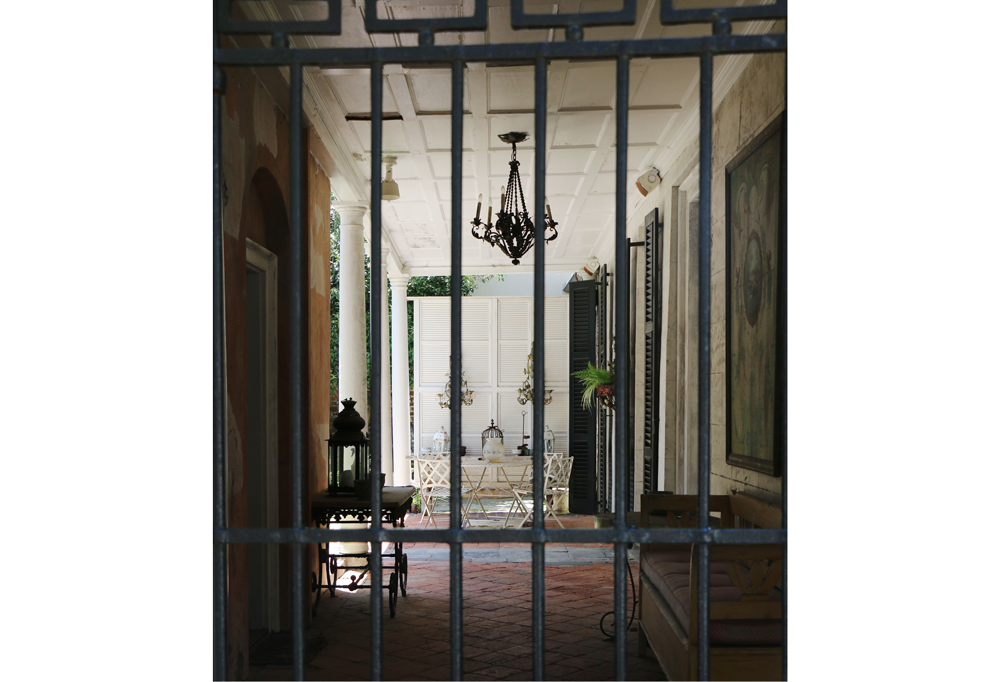

Looking through a portal into a piazza

Porches and piazzas are integral parts of the Charlestonian lifestyle, particularly in the summer heat. A piazza in Charleston is a side porch designed to provide outdoor living space, capture breezes, and shade windows. This is a key feature to a Charleston Single House, a house-type formed by narrow and deep lots. Often these homes are only one room wide on the side that faces the street, giving importance to the piazza which runs along each room. Image provided courtesy of Tyler Harbeson

The portal of the Isaac Mazyck Kitchen House, 86 Church Street

This green, shady courtyard is nestled between the two kitchen houses at the Isaac Mazyck House, now the Middleton Family Bed and Breakfast, which was constructed around 1783. These two outbuildings once held the servant’s quarters, kitchen, carriage, and necessary dependencies for the main house. Between the 1740s and 1820s, law required kitchens be separate from the living quarters to reduce the spread of fire.

A peek through the portal of the Gaye Sanders Fisher Gallery, 124 Church Street

An open door and a vibrant garden welcomes guests to this quaint art gallery located within the French Quarter District. Part of Charleston’s historic city center, French Huguenots once had warehouses and dwellings in this neighborhood, used by early Charleston merchants arriving at the docks off East Bay Street.

The portal of the William Hendrick's Tenements, nos 83-85 Church Street

The William Hendrick’s Tenement, called Cabbage Row, is a two-story stucco double tenement with two shopfronts on the ground floor and a central external hallway leading to the rear courtyard. The original 1 ½-story double kitchen building is visible through the archway. The structure was built around 1749 by Christ Church Parish planter William Hendrick as an investment. The building was damaged in the earthquake of 1886, and living conditions declined.

By the 1920s the surrounding neighborhood was a crowded and impoverished area whose residents were the families of freed slaves. Vegetables were grown in the courtyards and sold on the street, giving the name “Cabbage Row” to this building and the nearby 89-91 Church Street. Author DuBose Heyward, who lived a block away, made these poor living conditions infamous by using the building as the inspiration for “Catfish Row” in the novel Porgy and later the opera Porgy and Bess by Gershwin.

| contributed by Lora Shea |